General Matter, a new venture founded by Scott Nolan, currently a partner at VC Firm Founder’s Fund and formerly an engineer at SpaceX, is on a mission to restore America’s capacity to enrich uranium—a capability the U.S. has lacked for over a decade. This move comes amid growing concerns over the country’s dependence on foreign nuclear fuel sources, including strategic rivals like Russia and China.

The U.S. lost its domestic enrichment capacity because, by 2013, it had shut down its last major commercial enrichment plant, effectively outsourcing the process to foreign suppliers like Russia and Europe. While the U.S. has restarted limited domestic enrichment—Centrus Energy began producing low-enriched uranium (LEU) in 2023 in Ohio—it still lacks capacity for high-assay LEU (HALEU), importing 100% of its HALEU needs.

Backed by a $50 million investment from Founders Fund, the company brings together top engineering talent from SpaceX, Tesla, and the Department of Defense. Their goal is to develop scalable production of high-assay low-enriched uranium (HALEU)—a next-generation fuel critical for advanced nuclear reactors, and increasingly vital for energy-intensive industries like AI and advanced manufacturing.

So, what problem is General Matter trying to solve?

In the process of starting a nuclear fission chain reaction, enrichment is a key step. Enrichment is crucial because it increases the concentration of uranium-235 (U-235), the fissile isotope needed for nuclear fission, from its natural 0.7% to 3-20% for reactor fuel. Without enrichment, natural uranium can't sustain the chain reaction required for nuclear fission energy. Currently, U.S. imports most of the enriched nuclear fuel for its nuclear reactors from strategic rivals like Russia. General Matter is aiming to reduce this dependency and instead develop America’s domestic enrichment capabilities. Specifically, they are aiming to make HALEU, a specific variant of enriched uranium. Don’t worry if you don’t understand it. The rest of this article is all about the science of Nuclear Fission

In Part 1 of this series, I will cover the Fundamental Science and Process behind Nuclear Fission and how a Nuclear Power plant works, as this will help you understand and appreciate this story better.

In Part 2, I’ll cover the supply chain/ value chain, production and politics behind this story. That is, I’ll cover the history of Uranium enrichment in the U.S, why the U.S. lagged behind, and the geopolitics of all of it.

Let’s begin.

The process of Electricity Generation from Nuclear Fission Energy

The Science of Nuclear Fission

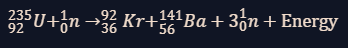

Nuclear fission is a process in which a heavy atomic nucleus, such as Uranium-235, splits into smaller nuclei when bombarded with a neutron. These splitting releases a significant amount of energy, primarily in the form of heat and kinetic energy of the resulting fragments and neutrons.

It's crucial to understand that not all uranium isotopes are created equal. In natural uranium, the fissile isotope uranium-235 makes up only about 0.7% of the total, with the non-fissile uranium-238 comprising over 99%. Since U-238 cannot sustain a chain reaction in most reactor designs, the concentration of U-235 must be increased. This is done through enrichment—a complex process that separates and concentrates the rarer, energy-producing isotope. This enrichment step transforms natural uranium into a viable fuel source capable of powering a nuclear reactor, typically boosting U-235 concentration to 3-5% for conventional reactors and up to 20% for advanced designs.

When a uranium-235 nucleus captures a neutron, it becomes unstable and splits—like a water droplet breaking apart—into two smaller nuclei, while releasing additional neutrons. These newly released neutrons can then collide with other uranium-235 atoms, triggering more fission events in what becomes a self-sustaining chain reaction if properly controlled.

The beauty of this reaction is in its incredible energy density. A single fission event releases roughly 200 million electron volts of energy—millions of times more energy than a typical chemical reaction. To put this in perspective: a uranium fuel pellet the size of your fingertip contains the energy equivalent of one ton of coal.

(If you want to look more into the science of Nuclear Fission, this video by Khan Academy explains Nuclear Fission in an accessible way: Nuclear fission | Physics | Khan Academy)

How does a Nuclear Fission Power plant work?

Now that you have an idea of the science behind nuclear fission, let’s move into how electrical energy is produced from Nuclear Fission.

Enriched uranium (we will focus more on enrichment later)—with an increased concentration of the fissile U-235 isotope—is fabricated into ceramic pellets and loaded into metal fuel rods, which are bundled into fuel assemblies.

Inside the reactor core, these fuel assemblies undergo controlled fission. Control rods made of neutron-absorbing materials like boron are inserted or withdrawn to regulate the rate of the reaction.

The heat generated by fission is captured by a coolant—typically water—circulating through the reactor core.

This heated coolant (either directly or through a heat exchanger) converts water in a secondary loop into high-pressure steam.

The steam drives turbines connected to generators, converting mechanical energy into electricity through the same principles that power coal and gas plants.

Putting it all together

So, to summarize the process, this is what happens in a nuclear power plant:

Nuclear fission releases a significant amount of energy, primarily in the form of heat and kinetic energy

The heat produced from fission is used to heat water.

The water turns into steam, which drives turbines.

The turbines generate electricity, converting nuclear energy into electrical energy.

What’s enrichment and why is it necessary?

As I have mentioned previously, the Uranium ore that is extracted through mining contains only about 0.7% of U-235, which is insufficient to sustain a chain reaction in most reactors.

Enrichment increases the U-235 concentration to 3–5% for use in conventional light-water reactors, or up to 20% for HALEU fuel, which is being developed for advanced reactors that offer improved efficiency, compactness, and longer fuel cycles. Enrichment ensures that the fuel has enough fissile material to maintain a sustained and controlled chain reaction, enabling continuous power generation.

The Uranium Enrichment Process in details

Let's explore the main enrichment methods used throughout history and today.

Gaseous Diffusion Method

Gaseous diffusion was the first large-scale enrichment method developed during the Manhattan Project and dominated the industry until the late 20th century. In this process, uranium is first converted into uranium hexafluoride (UF₆), a compound that becomes gaseous at relatively low temperatures. This gas is then forced through a series of porous barriers or membranes. Since molecules containing U-235 are slightly lighter than those with U-238, they move slightly faster and have a higher probability of passing through the barriers. Each passage through a barrier only provides a tiny enrichment effect, so the process must be repeated through thousands of stages in massive facilities that consume enormous amounts of electricity. While historically important, gaseous diffusion plants have been phased out in most countries due to their inefficiency.

Gas Centrifuge Method

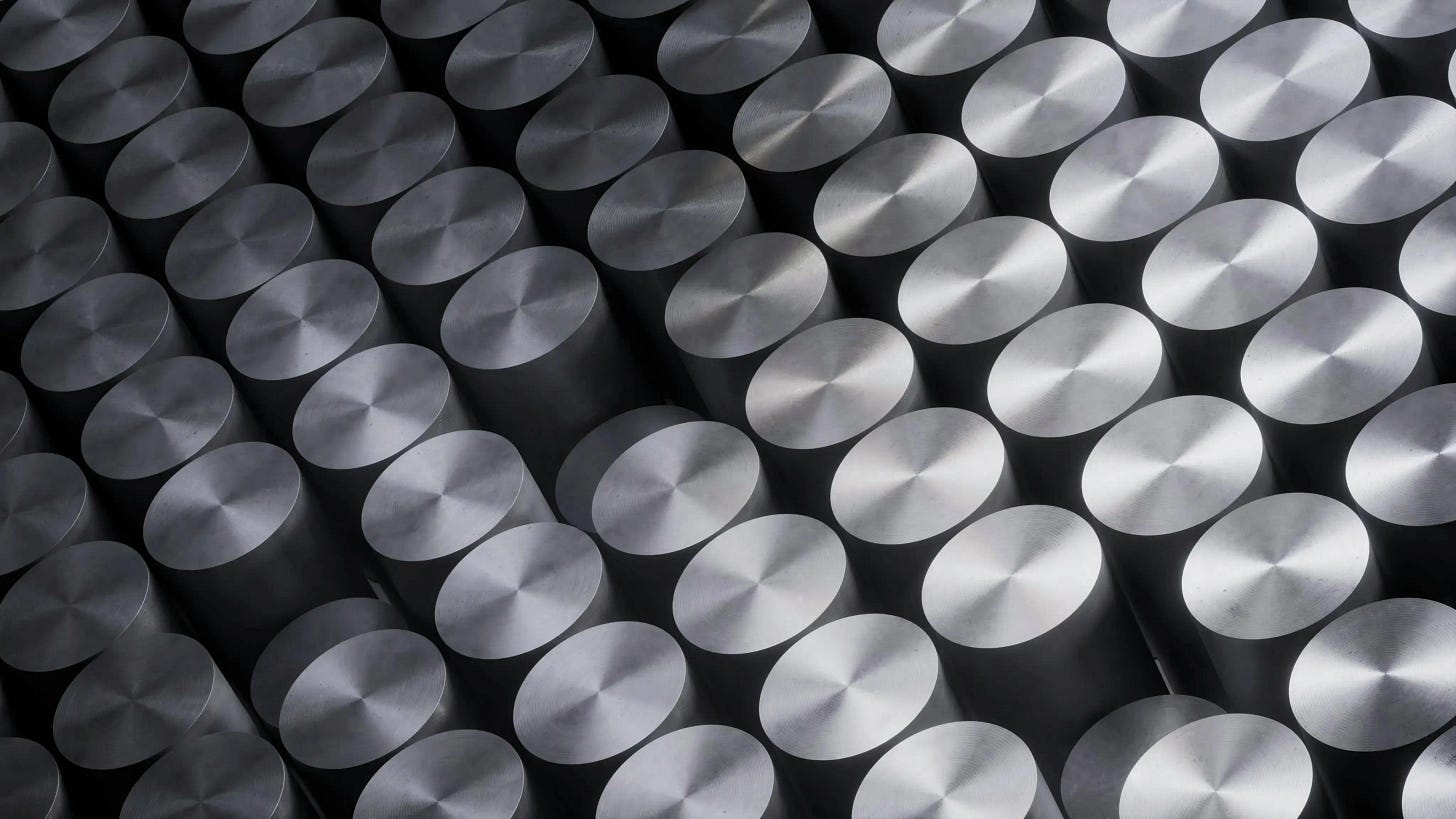

The gas centrifuge method represents the current industry standard for uranium enrichment worldwide. Like gaseous diffusion, it begins with uranium in UF₆ gas form, but instead uses the principle of centrifugal force. The gas is spun inside cylindrical rotors at incredibly high speeds—up to 100,000 RPM. This creates a strong centrifugal field where the heavier U-238 molecules are pushed toward the outer wall while the lighter U-235 molecules concentrate near the center. Small scoops collect the slightly enriched gas from the center and the depleted gas from the edges. Multiple centrifuges are connected in series and parallel arrangements called "cascades" to progressively increase enrichment levels. This method is significantly more energy-efficient than gaseous diffusion, requiring only about 5% of the electricity for the same enrichment output, which is why it has become the dominant technology.

Laser Enrichment Method

Laser enrichment represents the cutting edge of uranium enrichment technology. This approach exploits subtle differences in the electronic or vibrational energy states between U-235 and U-238 atoms. When precisely tuned lasers are directed at uranium vapor or gas, they can selectively excite or ionize only the U-235 atoms due to their slightly different electron configuration. Once excited or ionized, the U-235 can be separated using electromagnetic fields or chemical reactions. The two main variants being developed are Separation of Isotopes by Laser Excitation (SILEX) and Molecular Laser Isotope Separation (MLIS). Laser methods promise much higher efficiency and potentially lower costs than centrifuges, but the technology remains challenging to implement at industrial scale. Companies like General Atomics and Global Laser Enrichment are currently working to commercialize these technologies.

Levels of Enrichment

After enrichment, uranium is categorized based on its U-235 concentration:

Low-Enriched Uranium (LEU) contains between 3-5% U-235 and serves as the standard fuel for most operating nuclear power plants worldwide.

High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU) contains between 5-20% U-235 and is required for many next-generation reactor designs, including small modular reactors and microreactors. HALEU enables more compact reactor cores, longer operating cycles, and higher temperature operation, but production capacity remains limited globally. (This is the variant that General Matter plan to make.)

Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU), containing over 20% U-235, is primarily used in research reactors, naval propulsion systems, and weapons applications. International safeguards strictly control this material due to its potential for military applications.

Won't a higher enrichment created by HALEU make the reaction uncontrollable, potentially turning it into a bomb?

While higher enrichment increases the likelihood of fission reactions, it does not automatically make the reaction uncontrollable or turn it into a bomb. The difference between a nuclear reactor and a nuclear bomb comes down to how the chain reaction is managed.

In reactors, the rate of fission is carefully controlled using moderators (like water or graphite) and control rods (which absorb neutrons). On the other hand, in a bomb, the chain reaction is designed to be uncontrolled, allowing an exponentially growing number of fission events in milliseconds, leading to an explosion.

Reactors typically use Low-Enriched Uranium (LEU) (~3-5% U-235), making chain reactions easier to control. Even High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU) (~5-20% U-235) can still be used safely in reactors designed to handle it. Weapons-Grade Uranium (~90% U-235) is necessary for a nuclear bomb because the chain reaction must sustain rapid fission.

So, even if a reactor has higher enrichment (HALEU), it is built with safety mechanisms, such as coolants, control rods, and neutron-absorbing materials, which slow down the reaction and prevent runaway conditions. A bomb, on the other hand, is engineered for a rapid, uncontrolled reaction, meaning critical mass and compression techniques are used to make fission happen at an explosive rate.

So, where does General Matter fit into all of these?

High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU) is the variant of Uranium that General Matter plans to make.

From Bloomberg:

General Matter has raised $50 million in a funding round led by the firm Founders Fund to make high-assay low-enriched uranium, or HALEU…. The Los Angeles-based startup — which has been operating largely under the radar until now — aims to bolster the nation’s nuclear energy industry

General Matter plans to produce HALEU by enriching uranium to 19.75% — just below the 20% threshold under regulations, meaning it’s not weapons-grade. The levels will be meaningfully higher than the 5% used in most nuclear power plants today. The company aims to help power the new generation of advanced reactors that researchers hope will come online over the next several years.

Interest in nuclear power has surged around the world in recent years. Many countries and companies are looking at atomic energy as a way to secure clean and stable electricity, particularly as demand for energy is expected to rise on back of artificial intelligence use and data center expansion. In the US, investors have backed several new companies developing next-generation reactors — such as small modular reactors — with more startups looking to bring their designs to commercialization.

What’s the state of Uranium enrichment in the U.S?

The United States relies heavily on imports for its nuclear fuel supply across various stages of the fuel cycle.

For Uranium Concentrate (U3O8), imports accounted for 99% of the 32 million pounds of U3O8 used in 2023 to make nuclear fuel in the U.S., with only 0.05 million pounds being domestically produced.

For LEUs, U.S. nuclear power plant owners and operators deliver natural uranium (in the form of U3O8e) to enrichment facilities. In 2023, 61% of this natural uranium feed was sent to foreign enrichment suppliers, while 39% went to U.S. enrichment suppliers. This means that 61% of the enrichment service for the majority of the natural uranium destined for U.S. reactors was performed outside the United States, thus implying its foreign dependence for LEU fuel.

For HALEU, the U.S. has historically been almost entirely dependent on imports. Russia is the primary, and effectively the only, country with significant commercial-scale HALEU production capacity. Domestic U.S. production of HALEU only began on a small scale in late 2023, so virtually all HALEU used or stockpiled in the U.S. to date has been imported, predominantly from Russia. Though there has been efforts made here apart from General Matter. Centrus Energy is actively involved in HALEU production at its American Centrifuge Plant in Piketon, Ohio. In June 2021, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved a license amendment for Centrus, making it the first U.S. facility licensed for HALEU production (enrichment up to 20% Uranium-235). In late 2023, Centrus Energy began producing HALEU at its facility in Piketon, Ohio, marking the first domestic production of this material in over 70 years. The Piketon plant is the only U.S. facility currently licensed to enrich uranium up to 19.75%, the level required for HALEU (read more here)

All these points to the conclusion that U.S is heavily dependent on foreign suppliers for Uranium fuel and Nuclear fission energy in general. And this is the exact problem that General Matter is aiming to solve.